Savoring Literary Sentences

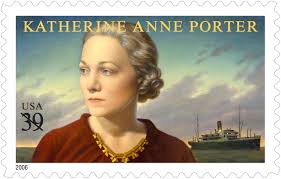

Do you have a favorite sentence from literature? Brian Dillon, in his essay "On a Wonderful, Beautiful, Almost Failed Sentence by Virginia Woolf," writes about the first sentence of Woolf's essay "On Being Ill." One that I admire tremendously can be found in Katherine Anne Porter's great short story "Theft." It comes just after the protagonist, tired of arguing, tells the person who stole her purse just to "keep it. . .Keep it if you want it so much."

"In this moment she felt that she had been robbed of an enormous number of valuable things, whether material or intangible: things lost or broken by her own fault, things she had forgotten and left in houses when she moved: books borrowed and not returned, journeys she had planned and had not made, words she had waited to hear spoken to her and had not heard, and the words she had meant to answer with, bitter alternatives and intolerable substitutes worse than nothing, and yet inescapable: the long patient suffering of dying friendships and the dark inexplicable death of love — all that she had had, and all that she had missed, were lost together, and were twice lost in this landslide of remembered losses."

The list, ascending from minor losses to huge ones, calls to mind "One Art," Elizabeth Bishop's great poem that similarly lists losses of increasing importance. Although Porter's is a prose rendition, it's as lyrical as a verse poem, its repetitions, alliteration, and rhythms meticulously layered.

As the increasingly abstract and important losses are named, the tension at stake grows too, like a verbal game of Jenga. I'm holding my breath with suspense by the time I reach the twinned nouns, constructed in parallel, each with two comma-less adjectives and an "of" phrase that align suffering with death--"the long patient suffering of dying friendships and the dark inexplicable death of love." Here at "love" everything pauses, maximally balanced. It's evident that this is what has been bothering the speaker all along. Underneath the edgy, restless reconstruction of her evening that has carried the story along so far, as the main character tried to figure out what became of her purse (and in the course of that, revealed a lot about her finances, work, and relationships), what was really disturbing her was the end of a love.

It's interesting that this sentence, like the Woolf sentence Dillon discusses, also arrives at a critical dash. My students will attest that I'm enamored of dashes. But while Woolf's dash throws things out of whack (at least in Dillon's view), this dash starts a perfect toppling, a cascade--a landslide, if you will, to pick up the passage's own metaphor. The clause that follows is beautifully aligned and nested: the having and the missing, the losing of both, the initial loss and the second stab of pain that happens when the "landslide" is remembered.

How often do you run into a sentence that not only presents a metaphor but also acts it out? Virtuoso stuff, in my book.