Tilling

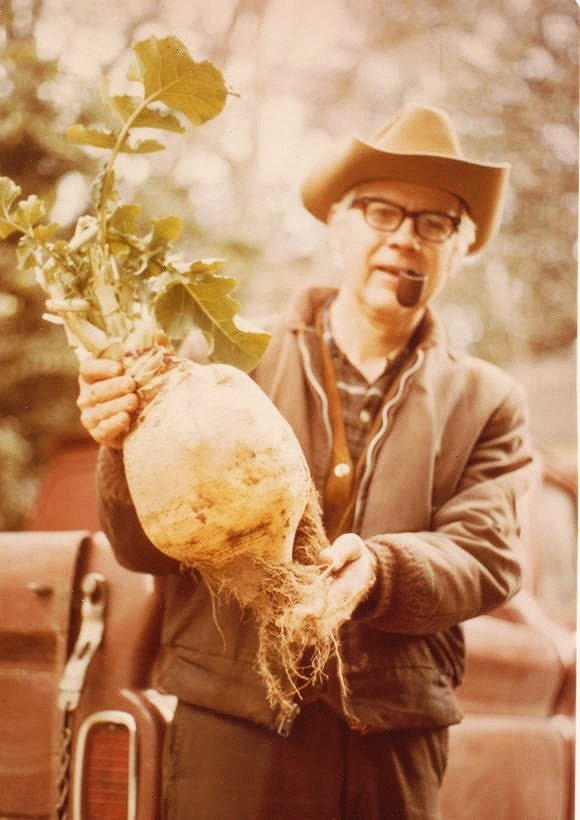

Massive rutabaga!

I used to love helping my father in his vegetable garden. It had several locations over the years—first on our farm northwest of Alexandria, between the Red River and the levee, and later at our home south of town, where the yard itself had space enough for a garden. The central Louisiana loam was rich and rock-free (something I didn’t appreciate fully till I moved to the stony ground of Little Rock), and the climate was mild enough to support a host of vegetables in every season, from cool-weather greens, carrots, leeks, Brussels sprouts, and cauliflower, to a summer bounty of tomatoes, peppers, eggplants, string beans, and okra. Farm-to-table eating was the norm at my parents’ house. Every day the kitchen counter next to the door would get piled with fresh vegetables. Even after my mother whisked them away to her side of the kitchen to be washed and dressed and concocted into supper, crumbs of sugary dirt littered the space beside the sink, beneath the clippers and the old work basket that sat waiting for their next trip outside.

In 2011 when my father died, it seemed fitting to return his ashes to that same dirt—not literally in the garden, I mean, but to a family plot a short distance away. Here’s a poem about that from my collection The Wheel of Light.

The Burial

He who taught me to break the lumps of dirt between my fingers,

pulling out weeds with the tines of a planting-fork,

to level and smooth the surface, then draw a groove

with the tip of the trowel, the hoe for a straight-edge—

he who shared with me the packets of seeds, tearing their corners

with a grimy thumb, and showed me the way to shake them not in clumps

but evenly spaced, though the line didn’t have to be perfect,

he said, because later we’d thin the plants—

he who peered with me at the seeds in their dirt beds,

some specks, some hard-shelled, and some like little beans,

had me cover them with their fine dirt blanket,

then pat and tamp the soil in the row we had made,

and stood up with me to survey it, our flattened mound

from which in time the shoots would poke,

so that visions of green profusion fed our minds

even then, as we brushed the dirt crumbs off our jeans—

we planted him in the ground today, in a hole my brothers dug,

pushed the loam down over his box with our palms, with the heels

of our hands, patted and tamped it smooth, the way he liked,

then stepped back to gaze at the blurry sight of what we had made.

Although some would say it was just the wind

stirring the leaves overhead, I believe I heard him sigh

as he settled, shifting his ashes and bone bits this way and that,

nestling into the pockets of dust like a satisfied infant laid to sleep.