10 Great Reads of 2017

Here--in no particular order--are the ten most memorable books from my 2017 reading.

Jane Alison, Nine Island

This “nonfiction novel,” as the writer has termed it, shouldn’t even work as a novel—I kept wondering how it held my attention at all, much less in such a captivating way. It’s about the stultifying existence of a woman living among much older people in a fancy high-rise in Miami Bay. She swims, translates Ovid, and contemplates her isolation while waiting for the next great storm that will inundate her and her small circle of intimates (which includes a stranded Muscovy duck). The book bears some interesting resemblance to Henning Mankell’s After the Fire, which I’m reading now. Both books have a marvelously torpid plot, an environmentally degraded coastal setting populated by elders, and a protagonist who’s cynical, solitary, and preoccupied with footwear.

William Finnegan, Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life

A thoroughly absorbing memoir of a New Yorker writer with a surfing obsession—or rather, a lifelong surfer who happens to write for The New Yorker. The story ranges from Hawaii to San Francisco to other wave meccas around the globe. The writing is excellent, with surf culture and settings compellingly shown. Even if I never get on a surfboard, these superb descriptions have at least shown me what it’s like.

Viet Thanh Nguyen, The Sympathizer

Terrific novel, well deserving its Pulitzer. The story of a North Vietnamese spy, this is more than a war novel; it’s a story of duality, or plurality—of living as other in a dominant culture, with the complex layers of consciousness that rouses. The writing is excellent, with rich, sly wordplay reminiscent of Nabokov.

Mohsin Hamid, How To Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia

A wonderful, absorbing read—not a financial self-help book, as Hamid said one ill-prepared radio interviewer mistakenly thought. The novel purports to be an instruction manual on rising from poverty to wealth in a war-torn Middle Eastern country. The supposed examplar of this lesson is the hero of this dry, dark, meticulously composed book.

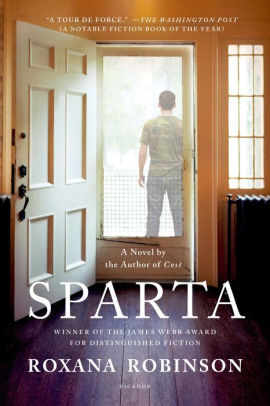

Roxana Robinson, Sparta

A young Marine officer returning from his deployment to Iraq tries to regain his foothold in American life. His effort; his intelligence; his rage; his upstate New York family; his college girlfriend; his assessment of the turmoil in Iraq; his memories of training, service, and trauma—all are intensely, humanely, believably rendered. I’m now going to read Robinson’s other novels.

Bruce M. Petty, Saipan: Oral Histories of the Pacific War

This read surprised me the most. It was chosen as background material for the veterans’ book discussion series that I’m involved in. The print was minuscule, and I thought it would be a drag, but I found myself fascinated by the first-person accounts of so many individuals—Chamorro, Spanish, Japanese, other Pacific Islanders, and Americans—who lived through the deprivations and drama of those days. I will never forget some of the descriptions, horrors, and emotions recounted.

Yusef Komunyakaa, Dien Cai Dau

Komunyakaa’s 1988 collection was another book selected for the veterans’ book discussion project, and the taut, shimmering slices of Vietnam war experience, seen mostly through the eyes of U.S. combatants, hold up very well. It was moving to hear veterans discuss these poems and, in particular, to hear one veteran read “Facing It” aloud.

Mohsin Hamid, Exit West

Hamid outdoes himself with this novel, my favorite book of 2017 (and the only one on my list also on President Obama’s year-end list). This is an epic tale of the human migrations happening around the globe, with a narrative focus on one pair of lovers in particular. Hamid is an exquisite writer, timely and timeless, charged with feeling but never polemical. There are wonderful passages here on human economic conditions, the refugee experience, Britain, Europe, and United States history, astutely observed...the elements of magical realism serve actuality well.

Sy Montgomery, The Good, Good Pig: The Extraordinary Life of Christopher Hogwood

This delighted me as an audio-book, narrated by Xe Sands, whose wry but not overly precious voice was well suited to the material; I wonder if it would have been as charming if I’d read it on the page. At any rate, it’s the story of a runt pig adopted by a couple on a New Hampshire farm. Christopher’s narrative also provides the frame for revelations about the author’s life as a nature and science writer, including her complicated relationship with her rigid parents, her feelings for animals, and the oddball community she and her husband find in their rural home. This is a great listen for all animal-lovers and is appropriate for children as well as adults. (Amazingly, despite being about a New England runt pig who grows to, ahem, full maturity and changes lives along the way, the book never overtly alludes to Charlotte’s Web.) Montgomery is coming to Hendrix next fall, so I’m particularly interested in her life and work.

Rinker Buck, The Oregon Trail: A New American Journey

In 2011 Rinker Buck and his brother drove a mule wagon across one of the original routes of the Oregon Trail, from Missouri to Oregon. This book chronicles their trip, with plentiful digressions about such things as the history of mules in America, trail deaths, and Mormonism. The audiobook I listened to was narrated by the author, who is not that great a reader; his draggy voice and frequent pauses grated on me until I was saved by my son’s suggestion that I increase the playback speed to 1.5. I started listening to this book on June 1 and finished in September—a seasonal span almost identical to most pioneers’ trips west, and to Buck’s own—and at times I felt it was an uphill slog (“Oh my God,” as I trudged up Shamrock Drive, “are we not yet to the Continental Divide?”). But on balance I enjoyed the trip, and much of the scenery and history continues to haunt me.

Greg Brownderville, A Horse with Holes in It

Fans of Brownderville will be glad that his third volume of poetry bears some of the hallmarks of his first two books: it’s full of Arkansas folklore, nature, and roots culture, it’s laced with humor and allusion, and it includes a beautifully executed variety of poetic forms. What’s new this time around is a restless, seething angst—as if the central figure of these poems has lost his bearings (could the wunderkind be approaching middle age?) and is groping through an urban wasteland (dare we call it Dallas?), trying to recover something vital and authentic. My review of this book will appear in Arkansas Review this spring, so I won’t say more here except that these poems are ones you’ll want to dwell with and return to.